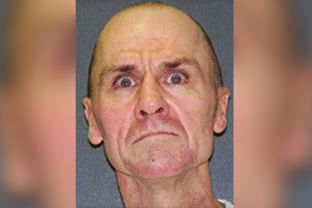

A Henderson County court will be asked to determine if an inmate on death row for a 2007 double murder is mentally competent enough to legally be executed.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals continued its stay of execution Wednesday for Randall Mays, who murdered a sheriff's office investigator and deputy in a shootout. He was scheduled to die in March, but the court intervened after his attorneys argued that his competency has not fully been evaluated.

A 2007 U.S. Supreme Court ruling bars execution of inmates who do not understand that they are about to be put to death and why they were condemned.

According to court documents, Mays told an attorney in February that he heard voices connected to "evil spirits" and could not explain why he was on death row.

Mays has a history of mental illness dating back to 1983, when the 56-year-old was involuntarily committed to Terrell State Hospital, court documents show. He was described as "actively psychotic," delusional and combative.

Mays was returned to the state-supported hospital in 1985 by law enforcement, who found him under the influence of crystal methamphetamine and experiencing "auditory hallucinations."

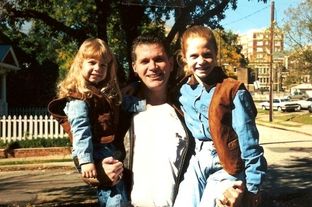

On May 17, 2007, several Henderson County sheriff's deputies responded to a domestic violence call at a home in Payne Springs. Mays and his wife, Candis, were having an argument.

When a deputy tried to arrest Mays, he retreated into his home, emerged with a rifle and later began shooting, drawing more deputies to the scene. They returned fire, but Mays killed Inspector Paul Steven Habelt and Deputy Tony Price Ogburn, and wounded Deputy Kevin Harris. Mays eventually surrendered after being shot.

After his 2007 arrest for the double murder, Mays was sent to East Texas Medical Center to be treated for his gunshot wound from the confrontation. Nurses said he at one point spoke to someone who was not present, and at another "he was lying in bed screaming for help and stating that he thought people were trying to kill him and that he thought they had killed his wife."

After that stay, Mays was discharged to Smith County Jail, where staff documented that he suffered from mental illness. He later was diagnosed with Organic Brain Syndrome, which is described as a precursor to dementia.

At trial, Mays expert and lay witnesses testified with similar examples that he showed signs of mental illness.

Dissenting from the court's 7-2 decision to extend his stay, Presiding Judge Sharon Keller said in an opinion Mays has provided evidence showing mental illness, but none that shows he doesn't understand that he is about to be executed and why. Judge Lawrence Meyers joined Keller's opinion.